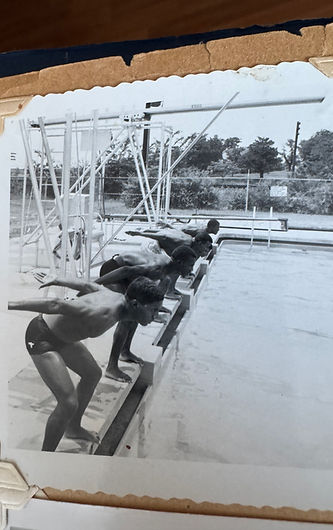

The Drew Park Pool

Sharks…

Columbia, SC

…..In Their Words

Gary Kimble

Index

1. Stanley McIntosh

2. Ellis R. Pearson

3. Benjamin Lindbergh Jeffcoat

4. Jimmie Ruff

5. Chris Cochran

6. Gary Bell

7. Stephen McIntosh

8. Tony Thomas

9. Delano “Domino” Boulware

10. Moses Hopkins

11. Thaddeus Bell

12. Harvey Dorrah

13. Regina Brandyburg

14. Freddie Brandyburg

15. Talmadge Dixon

16. Charles Bolden Jr.

17. Robert Bradley

18. Howard Simmons

19. Mark Harkness

20. Montez Martin

21. Milton Kimpson

22. Edwina Fields

23. Wesley Kennedy

24. Carolyn Fair

25. Judy Fair

26. Ronald Anderson

27. Virginia Brown

28. Delores Brown

29. Karen Brown

30. Henry Kennedy

31. EW Cromartie

32. James “Garrett” Garrett

33. James “Foxy” Evans

34. David Whaley

35. Johnny “Rock” Edward

History has the potential to lift or devastate your spirit. Our history requires us to see both the good and the evil and to know right from wrong. As Dickens wrote in A Tale of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. History demonstrates that extreme contradictions can exist at the same time. Such is the story of the Drew Park Pool Sharks of Columbia, South Carolina.

With Abraham Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation” signed on January 1, 1863, enslaved people in the Confederate states were declared free. The government, as stated in the document, would recognize all enslaved persons in the rebelling states. In addition, the proclamation allowed Black men to serve in the military which strengthened the Union army. The Civil War ended on May 26, 1865 and with it, the dissolution of the Confederate States of America.

Following the Civil War, as early as later in 1865, and after the ratification of the 13th Amendment, Southern legislators passed state and local laws that enforced racial segregation throughout the late 19th century and early 20th century. Many of these laws remained in effect until 1965. The laws were designed to disenfranchise and remove any political and economic gains made by African Americans during the Reconstruction era. Reconstruction was the period dominated by the challenges of the abolition of slavery. The laws were commonly referred to as Jim Crow Laws. Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the former Confederate states. They detailed where and how formerly enslaved people could work, and how much they could receive in compensation. The laws basically put Black citizens into indentured servitude and they took away voting rights and controlled where they lived and how they traveled. The U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 upheld Jim Crow laws and laid out its “separate but equal” legal doctrine concerning facilities for African Americans, in the case, Plessy v Ferguson. Although in theory, the “equal” segregation doctrine governed public facilities and transportation, facilities for African American citizens were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to the facilities for white Americans. Sometimes there were no facilities for the Black community. Frequently, former Confederate soldiers worked as police officers and judges, making it difficult for African Americans to win court cases and ensuring they were subject to Black codes.

In 1954, the segregation of public schools was declared unconstitutional in the landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v Board of Education of Topeka. Any remaining Jim Crow laws were overturned by the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1911, the City of Columbia Parks and Recreation Department opened the Maxcy Gregg Park. The park was named for a former Confederate general. In 1949, a swimming pool and bathhouse was dedicated. The pool was later renovated. It became a fifty-meter pool, key for competitive swimming, as those are the official lengths for long-course events. At its previous length, swimmers’ times did not translate to those at regulation pools and top competitive events shunned the pool for that reason.

Drew Park opened in 1946 as a segregated recreational space for African Americans. It was originally called Seegers Park for the white family who had previously owned the land. To offer a more representative name, it was renamed posthumously in 1952 for Dr. Charles R. Drew, a prominent African American surgeon who was a pioneer in the field of blood transfusions. A 50- meter/55-yard swimming pool was opened in May, 1950. The city hired Thomas Martin to manage the complex. More information regarding Thomas Martin will be forthcoming later. The swimming pool was a special point of pride for Drew Park due to the neighborhood’s highly successful men and women’s swimming teams, the Drew Park Pool Sharks. The Sharks swim team was officially established in 1952. Beginning on Memorial Day generally and through the entire summer ending on Labor Day, the Drew Park pool was for the community a lifesaving resource and many who swam there referred to as their “summer babysitter”. African American youth could go to the pool in the morning, stay through lunch and have parents pick them up following work. As the number of competitive swim teams of color were limited, and travel costs were prohibitive, the big event of the summer was generally the August intrateam swim meet competition. The meet drew a huge crowd of spectators and proud parents, relatives and neighbors cheering on their favorite swimmers in each of the various swimming events. In 2005, the Charles R. Drew Wellness Center opened offering the community a modern twenty-five-meter swimming pool, a gymnasium, a track, and a cardio workout center.

The writer recently found an AI-generated statement claiming, “There isn’t much information about all-Black swim teams in South Carolina.” In 2025, he hopes to change that.

Amidst all the negative issues surrounding the period of segregation, there was a committed group of individuals; really visionaries, who organized, managed and coached African American youth to successful and impactful swimming experiences that altered their lives forever. Individuals such as T.S. Martin, Charles Bolden, Nathaniel Stevenson, and James Ruff. It was due to their efforts, as well as other Black leaders that the Drew Park Sharks became a reality. All were known for their commitment to providing opportunities for Black youth in competitive swimming and aimed to promote swimming skills, foster teamwork, and encourage a love for the water in the community. The Sharks not only focused on developing athletes' swimming abilities but also emphasized the importance of education and community involvement. An essential focus that remains vital in 2025, particularly in areas where access to swimming has been limited.

Throughout the stories related below, you will read about the events the Sharks competed in during their swim meets as well as the individuals themselves. At Drew, different events were based upon the ages of the participants.

The following were the swim events at Drew for the various age groups:

Midget Boys and Midget girls:

50-meter freestyle; 50-meter breaststroke; 50-meter backstroke; 50-meter butterfly

Boys and Girls:

50-meter freestyle; 50-meter breaststroke; 50-meter backstroke; 50-meter butterfly; 100-meter freestyle; 100-meter breaststroke; 100-meter backstroke; 100-meter butterfly

Junior Men and Women:

50-meter freestyle; 50-meter breaststroke; 50-meter backstroke; 50-meter butterfly; 100-meter freestyle; 100-meter breaststroke; 100-meter backstroke; 100-meter butterfly; 200-meter freestyle; 200-meter breaststroke; 200-meter backstroke; 200-meter butterfly; 400-meter individual medley

Senior Men and Women:

50-meter freestyle; 50-meter breaststroke; 50-meter backstroke; 50-meter butterfly; 100-meter freestyle; 100-meter breaststroke; 100-meter backstroke; 100-meter butterfly; 200-meter freestyle; 200-meter breaststroke; 200-meter backstroke; 200-meter butterfly; 400-meter individual medley; 800-meters Freestyle (men only)

In the events at Drew, women and men swam separately. Most meets were all day on Saturdays. The Drew Park pool complex had, in addition to nine lanes, four diving boards. During meets, there were diving competitions for 1-meter and 3-meter springboards. On certain Sundays throughout the summer, the lifeguards, whether current, previous or inspiring lifeguards, performed a water show which truly was a “show” for the community. The divers utilized all four boards and performed synchronized diving routines. To add extra excitement and entertainment value, some of the dives involved criss-cross patterns with the divers jumping in front of each other as they dove into the water.

This writer was not a competitive swimmer, nor was he ever a member of a swim team. He swims for pleasure and for the health benefits which research emphasizes offers a comprehensive range of benefits for physical and mental health, making it an excellent choice for an active and healthy lifestyle. It is accepted by most that swimming:

-

strengthens the heart

-

improves blood circulation, reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases

-

enhances strength and endurance by engaging multiple muscle groups

-

reduces impact on joints due to the buoyancy of water making it suitable for people with arthritis

-

promotes flexibility and range of motion

-

excellent calorie-burning activity contributing to weight management

-

the repetitive and calming motions of swimming can help reduce stress and anxiety

-

swimming releases endorphins, which have mood boosting effects

-

regular swimming can improve sleep and reduce insomnia

-

relatively inexpensive exercise requiring minimal equipment

-

a low impact exercise, suitable for individuals of all fitness levels

As a non-competitive swimmer, at times during this writing, various individuals categorized the Drew Park pool and the swimming events using different lengths. This made for some confusion. So as not to further confuse the reader, one needs to understand the variations were really a personal preference as the description of the length of the events. Some individuals refer to the pool being 50-meters, while others refer to it as 55 yards. Specifically, some team members indicate they swam the 110, while others referred to it as the 100. The distances are virtually the same as 100-meters converts to 109.361 yards (110) and 50-meters converts to 54.6807 or 55 yards. Putting the distance into another context, the 110-yard swimming event is comparable to swimming 10 yards more than the length of a football field.

Not to minimize history in any manner, but this is not a story about racism and the negativity at the time of the Drew Park Pool Sharks. This is a story about the positive opportunity individuals experienced swimming as a member of the Drew Park Sharks. I would be remiss if I didn’t highlight the extensive influence that the parents of these swimmers played in their success, both as swimmers and for their lives in general. In their own words, I wish to introduce these former members of the Drew Park Pool Sharks.